Jonathan Blitzer Longlist Interview

9 October 2024

How does it feel to be longlisted?

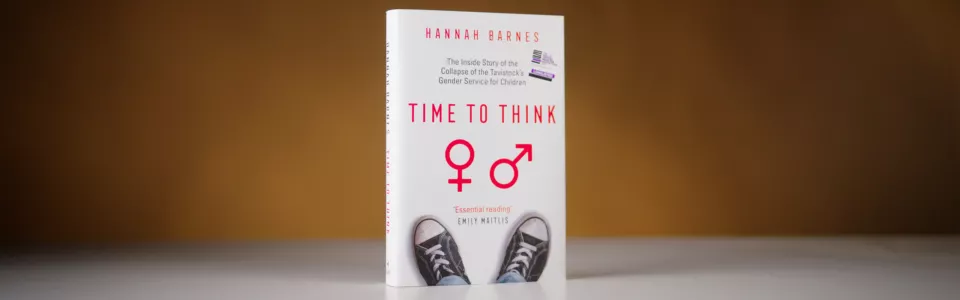

To say that I am feel over the moon to be longlisted would be an understatement. I feel honoured to be in such talented company and am delighted that the judges were able to see the book for what it is and what I aimed for: a forensic piece of investigative journalism, told with clarity and compassion, about an area of healthcare serving some of the most vulnerable young people in society. Writing Time to Think was without doubt the hardest thing I have ever done. For that effort to be recognised in this way is just wonderful.

How did you conduct your research?

Some of the research had been done before I signed the deal with Swift Press to write Time to Think - while making several films and writing articles on this topic for BBC Newsnight and the wider corporation. But ultimately this ended up being a very small amount of the overall research conducted. I’m not sure I can list everything that went into the book, but I can give a taster. I went through all the documentary material I could find in the public domain: going though every set of board minutes for the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, every Freedom of Information request, and press cuttings going back to the service’s beginning in 1989, for example. I read all the major academic papers that form the evidential basis for gender affirmative medical care in young people and submitted several Freedom of Information requests of my own. I contacted more than 60 clinicians who had worked directly with young people attending the Tavistock’s Gender Identity Development Service – hoping to gain a breadth and depth of accounts based on direct experience. I did the same with young people who had attended the service. I followed key legal cases live and spoke with as many people as I could with experience of both GIDS and the wider Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust. In the course of this, many were kind enough to share internal documents with me, as I gained their trust.

How different did you find writing a book from writing for a news programme?

I was not at all prepared for what writing a book would entail! In some ways it was similar: taking huge amounts of information, sorting it and transforming it into a clear narrative; writing to a deadline; checking and rechecking facts and sources. But, overall, it was very different to writing for a news programme, or factual documentary. For starters, it is an exceptionally lonely experience. In broadcasting you are almost always part of a team, even if it is a small one. You can bounce ideas off each other or simply let off steam. Writing a book is very much a lone project, even though I received enormous amounts of support from friends and family. Secondly, the timescale involved. Although I have generally worked on long form journalism, any given film of radio documentary might take weeks or even a couple of months, but not months on end. There was something different about the intensity too. With a Newsnight film for example, we tend to work very long hours in the days running up to transmission, but thankfully that spell is relatively brief. While writing, I experienced that level of intensity for months. All while looking after a newborn baby! I am used to working to deadlines – and I met mine for submitting the manuscript – but it took enormous discipline to divide a longer amount of time into milestones that had to be met so that I could deliver the book. And then there’s the depth of research. All my broadcast work is rigorously researched. It is double sourced at a minimum, checked, and re-checked. But the quantity of research required to fill 375 pages, and be seen as credible on such a controversial topic was very different. I wanted to be utterly transparent about where all the information had come from; that’s why there are 60 pages of references.

What do you hope clinicians of the future can learn from your research?

There are many things that clinicians can learn from what has unfolded at the Tavistock’s Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS). If my research teaches us anything, perhaps it is that even with the best of intentions, good, professional people can go wrong and make mistakes; it’s how they and others respond that is important. It became clear that the medical treatment on offer – puberty blockers – were not performing as we all believed it to be; they weren’t providing time and space to think and reflect. As one clinician, Dr Anna Hutchinson, points out, ‘Sadly, GIDS chose not to pause for thought.’ Instead, she believed that GIDS – for a time at least – was ‘routinely offering an extreme medical intervention as the first line treatment to hundreds of distressed young people.’

In addition, the young people predominantly GIDS’ help were not the same young people for whom the medical pathway towards gender transition was designed for. Doctors and other health professionals must reflect on changing evidence. If the patient population isn’t the same, then it might be that the treatment shouldn’t be the same. My research shows that one treatment pathway will not work for all of the young people seeking help around their gender identity.

I hope that the need to collect robust, and long-term data on this group of young people is evident and something that can be corrected moving forward. We know next to nothing about how 10,000 or so young people seen at GIDS have fared – both those who started a medical transition, and those who did not. We have no idea how many continued to identify as trans, and how many did not. How many medically transitioned and are happy, and how many went through the process only to regret it. I have spoken to people in each category – and their stories are in the book. It is only by monitoring outcomes and conducting proper research that the best care possible can be provided to each and every young person seeking help.

What are you working on next?

I’m looking forward to taking a short break at the end of this year before embarking on a completely new role for a different news organisation. I am leaving the BBC after 15 years in October and will be joining the New Statesman in January as Associate Editor and Writer. It’s an enormously exciting opportunity to write about all manner of things - in columns, long-read analysis, and investigations. I won’t give too much away, but it is absolutely my aim to continue exploring the subjects that many see as ‘too difficult’, but which we must discuss as a society. Life is complicated. There often aren’t easy answers, particularly to some of the thorniest issues of our time. And there are often many shades of grey. But we must be able to talk, to ask difficult questions, and try to understand. There is, and must always be, a place for impartial scrutiny and robust evidence-based journalism, even if it exposes uncomfortable truths in contentious areas.

10 April 2025

17 December 2024

19 November 2024