Jonathan Blitzer Longlist Interview

9 October 2024

How does it feel to be longlisted?

For me, Mr. B was a huge writing challenge. Because the life of an artist is the life of imagination, and the mysterious alchemy of art, I was obsessed with knowing Balanchine’s inner life, recovering his nature, his secrets, what drove him, and his dances. This is of course an impossible task – who can know the inner life of another (especially if he is dead!) -- but it is also in some way possible, if the writing sustains it. In telling the life story of George Balanchine, I found myself in the delicate space between fact and imagination; document and feeling, memory and history. The life – his life, my book -- lives or dies less on the facts (meticulously researched) than on the writing, which is why I am so very honoured to be nominated.

How did you conduct your research?

Balanchine has been one of the greatest intellectual, emotional, and spiritual encounters of my life. The research was an intense decade-long journey that really began a lifetime ago when I was a teenager and first set foot in a dance studio, saw and performed Balanchine’s dances, and watched him work. How could I have known then that the project of knowing him would take me to archives and places and people in Russia, Georgia, and across Europe and America; into the history of war, art, music, literature, jazz and African American dance, all of which influenced him greatly; into philosophy, Orthodoxy, Sufism, exile, the Cold War, and so much more.

I was especially interested in the testimony of dancers and I interviewed over 200 people who had worked with or known Balanchine and the other supporting characters in the book. His dances did not exist without dancers, and their presence –physical, emotional, and intellectual – profoundly shaped his life -- and my account of him.

But testimony and memory are not history, and I also did extensive archival research in Russia, Georgia, and in cities across Europe and America. Balanchine himself destroyed the evidence of his life as he went, and recovering him meant reading everything that was left, from letters, sketches and musical scores. to credit card receipts and passport applications. I also walked Balanchine’s path, and followed him to dance studios, theatres, and museums; hospitals, orthodox churches, restaurants and hotels; places where he loved, and places where he wept.

I read what he read: Cervantes, Goethe, Shakespeare, Ovid; Pushkin, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Gogol, Bulgakin; Mysticism, Neoplatonism, Spinoza, Sufism; I studied art that he drew on, from Russian Icons, to Renaissance painting, and the surrealists. I listened: to Bach, Mozart and Tchaikovsky; Stravinsky, Ives, Hindemith, Xenakis. And of course, I watched, and danced, his dances.

How much do you think the twentieth century shaped Balanchine's being and relationship to his work?

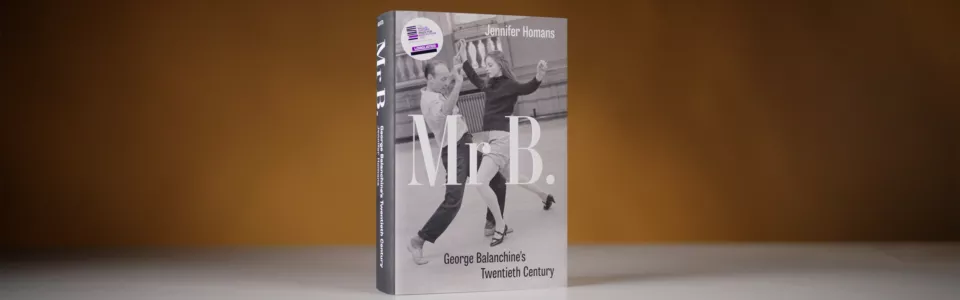

Profoundly. I subtitled the book “George Balanchine’s 20th Century” because he absorbed into his dances the century he lived through. He experienced WW1, the Russian Revolution, WW2 and the Cold War; he was in Berlin and Paris in the 1920s, and landed in NY in 1933 in the middle of the Depression. He lived through hunger and dispossession; statelessness and exile; epidemics and illness (he should have died of TB). He worked on Broadway, in Hollywood, and staged opera, theatre and the circus, and in 1948, he cofounded the New York City Ballet where, with his dancers, he made some of the strangest and most glorious dances to grace the modern stage.

I also subtitled the book “George Balanchine’s 20th Century” because his dances were his 20th Century – the one he created in art.

It took me 600 pages to answer this question, which is truly at the heart of the Mr. B.

What made Balanchine's iconic work so unforgettable and unique?

My best short answer to this question is to offer a quote from the book:

When the curtain went up on a Balanchine ballet, audiences did not "see a ballet"; they witnessed a group of dancers making their way through a living, shifting labyrinth of split-second choices, calculations, mistakes, regrets, adjustments, and consequences. It was alive and unpredictable, bound to music but also free within it. Class and rehearsal were for learning the steps and knowing the limits; but in performance it was up to the dancer to take on the complexities of the music and dance. Some dancers made more interesting guides than others, which is why who was dancing mattered terribly -- to us and to Balanchine. He made ballets for dancers to live in, and when everything worked, they ran free.

Or, as Balanchine put it, “this music, these dancers, here, now.”

What are you working on next?

I am working on a book I am tentatively calling “On Dancing.” I have started, but it is too muddy to say exactly what it is yet.

10 April 2025

17 December 2024

19 November 2024