Jonathan Blitzer Longlist Interview

9 October 2024

How does it feel to be longlisted?

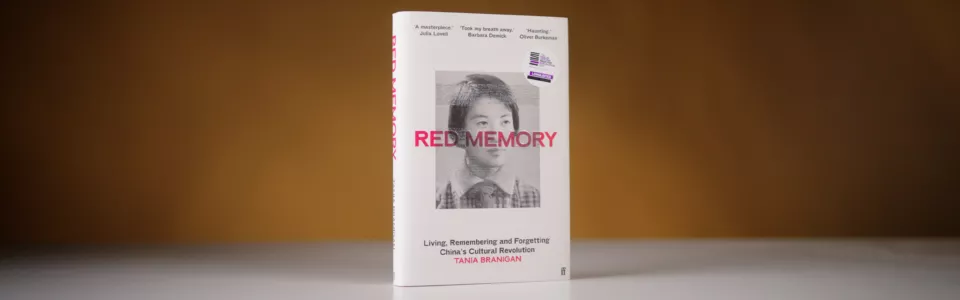

I spent ten years working on Red Memory without knowing whether anyone would read it: I never sold the proposal, but felt driven to write it anyway. So to find it longlisted alongside so many remarkable books, for a prize with so many winners I’ve loved – such as Nothing to Envy, Stasiland and H is for Hawk – is extraordinary. It’s wonderful, and very disconcerting.

How did you conduct your research?

I travelled across the country to visit museums and other sites but most of all, to meet survivors and spend hour after hour listening. What unites all the people in Red Memory is that they chose to remember when everyone else preferred to forget. I wanted to understand not just what happened to them, but how they saw it all; to be led, firstly, by what they chose to tell me, and how they told it, before delving deeper and asking them more. In most cases I met them multiple times, over months and years, and often, their stories overlapped. That allowed me to build up a much richer and more comprehensive picture of the era and what it means to people today – whether their overwhelming feeling is guilt, trauma or even nostalgia. Then there are all the people who aren’t mentioned directly in the book but whose experience informed it in so many ways. Those I met included Mao’s personal photographer, who captured both iconic images of the Great Helmsman and his private family moments – but then, like so many, was hounded in the Cultural Revolution. Several of them have died since we spoke; I was privileged to capture a part of history that is slipping away very fast.

Of course, I also benefited immensely from the wealth of research that’s been done by scholars and other researchers, both outside China and within. My reading stretched from personal memoirs and fiction through to in-depth studies of everything from Mao badges to mass killings. I hope that readers of Red Memory will turn to some of those books too.

In Red Memory, you delve into the personal stories of individuals who lived through the Cultural Revolution and its enduring impact on Chinese society. What was the most compelling or surprising story from your research that sheds light on how this tumultuous period continues to shape China today?

In political terms it’s hard not to see today’s China – in particular Xi Jinping’s concentration of power and axing of term limits – in light of his personal experience of the era, when his family was persecuted and he spent seven years labouring in bitter rural poverty. In psychological terms, the ongoing toll is encapsulated by the apparently mild-mannered young man who suddenly published a graphic account of killing one of his tutors. It was only after his family began seeing a psychotherapist that he learned that his father had watched as his grandfather was murdered by Red Guards. It speaks volumes about the secrets that families still keep, and their cost. The past refuses to be left behind.

What shocked me most, however, were the growing parallels between the Cultural Revolution and what I saw as I was writing – both in China and in the west.

Do you think there will be anther revolution of the same scale in China's future?

You could say that it’s already happened: in many ways the turn to the market was an equally abrupt and even shocking transformation for people in China. Zooming out, the Communist party’s whole history is a reproach to predictions – it started with 13 men meeting in a backroom in Shanghai, and against all the odds, a century later, it has almost 100 million members and runs one of the most powerful countries on earth. Of course, that means that authorities are unbelievably vigilant about new organisations, and their surveillance capabilities are better than ever. A top-down campaign, of the kind unleashed by Mao, is possible – but Xi Jinping doesn’t relish disorder so it’s hard to see him handing power to the masses in the same way. People are also much more sophisticated, cynical and individualistic now.

The Cultural Revolution certainly wouldn’t happen again in the same form - it was a product of a particular time and place. But human nature doesn’t change and that can produce immense and, yes, often destructive transformations. The Cultural Revolution doesn’t just hold lessons for China, but for all of us.

What are you working on next?

As foreign leader writer at The Guardian I have the pleasure of talking to immensely smart people every day about the big issues facing the world. Beyond that? I remember joking that I was the only journalist in Beijing not writing a book. So, I’ve learned that it’s probably best to keep my mouth shut when it comes to plans

10 April 2025

17 December 2024

19 November 2024