Jonathan Blitzer Longlist Interview

9 October 2024

How does it feel to be longlisted?

It was a total surprise, since my publisher very nicely did not tell me I was nominated. I am grateful for the recognition and the very hard work of the jury, even as I know that the news of nominations, longlists, and shortlists are best kept away from an author like me. Wake me when it’s all over. Better yet, don’t wake me at all. Let me dream that all that matters is the writing.

How did you navigate the complexities of memory and forgetting in your writing?

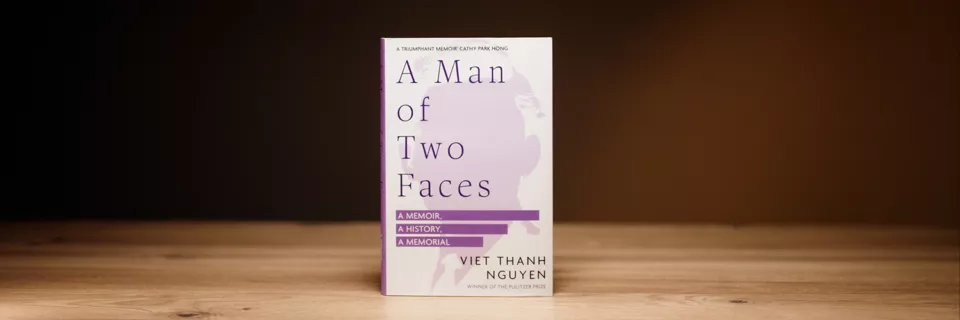

I wrote a book called Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, where I worked through the ethical complications of remembering and forgetting for nations and, to a lesser extent, individuals. My basic conclusion was that we have to remember our own side; we have to remember the other side; and we have to remember that we like to remember our own humanity and deny the humanity of our enemies. Given that, individual and collective memory is generally self-serving and unreliable, and we have to work actively to overcome those tendencies or at least make them visible. That’s what I try to do in A Man of Two Faces, which is about what I have remembered and what I have forgotten. The book does not try to make up for my glaring absences of memory, but instead points them out and incorporates the void of forgetting into who I am and my faulty knowledge of myself. The book, like most worthwhile memoirs, is ultimately a betrayal of myself, even if it might also be a betrayal of others.

How did you find balancing humour and lyricism with the heavy themes of refugee-hood and colonisation in your memoir?

If readers have read my novels. The Sympathizer and The Committed, they know those are spy and gangster novels with lots of violence, drugs, drinking, fornicating, and philosophising, mixed with satire, absurdity, and jokes of both the high and low (very low) kinds. Shakespeare taught me that you can use comedy to alleviate tragedy in a high-minded and artistic way, while my children teach me that lowbrow jokes are the stuff of life and love and laughter and just getting through the sometimes very long day. Politicians and the pompous, of whom I encounter too many, remind me that humour is necessary to puncture the pretensions of the powerful, from the petty powerful in our daily lives to the truly, frighteningly powerful types who threaten to shorten our lifespans and those of others. A joke makes all the inevitable foulness of humanity go down easier, while writing well, even lyrically, buoys us up, carries us along, and shows us that we are capable of creating and enjoying beauty even in discussing and surviving the worst of things.

What insights have you gained about cultural power through your experiences and how are they reflected in you memoir?

Stories matter. Stories matter so much that the powerful appropriate that power for themselves, via their catchy slogans and seductive narratives about how the world is better because of the powerful, while seeking to persuade the less powerful that stories don’t matter. So just go study something that will make you a useful worker, and leave the imagination to us. We will use culture to justify our power, while this power will allow us to shape the culture.

Culture is always used to make us feel better about our particular ethnic, religious, racial, national, or political identity, especially in the face of those other people who are not as human as we are, for our humanity is the best humanity of all, and our culture proves it. And since we are human and they are inhuman—whoever they are, because they will change as needed—we are then justified in unleashing all manner of inhuman violence on them, both of the fast and spectacular kind that we will sometimes see on our screens but most often of the slow and grinding kind that we will never see or want to see. But what does it matter, what happens to them? We have culture, and they do not.

This is why I believe that writers, and other storytellers and artists, will always matter. We use stories to destroy others in our imagination, which allows us to feel perfectly fine when we destroy them in real life. So, we will need stories and storytellers to attempt to save others, even though they are often capable of saving themselves. Ultimately, though, we need stories to save ourselves and what we like to think of as our souls and our humanity, despite all the evidence of our history and present that our humanity often goes missing.

What message do you hope readers take away from your memoir about the promises and realities of the American Dream?

The United States is a settler colonial country, built on two conflicting, contradictory impulses of beauty and brutality. The beautiful part is the one about democracy, liberty, equality, opportunity, and so on. The brutal part is how none of those things would have been possible without colonisation, enslavement, genocide, occupation, and perpetual war from the very origins of the country to the present. Americans don’t like to acknowledge this settler colonial history and reality. Instead, they call settler colonialism “The American Dream,” a brand that has been offered for sale to the rest of the world and given for free to Americans. Nothing is ever so dangerous as that which is offered for free.

Americans are not unique in wanting to believe the best about themselves, while erasing, ignoring, or excusing the worst. Most nations feel the same way, as do most individuals. If non-Americans can nod at my critique of AMERICATM, and even laugh at times, I hope they also think about how their own nations and cultures might participate in the same dynamic of selective self-regard. But although all nations are messed up in their own ways, not all nations inflict the same damage. That extraordinary power to damage does make the United States rather exceptional at this moment. I am the beneficiary of that power, as an American citizen, but perhaps that makes it even more crucial for me, as well as my fellow Americans, to speak out about the consequences of that power. Only by acknowledging the horror can we rightfully speak about the possibility of hope.

10 April 2025

17 December 2024

19 November 2024